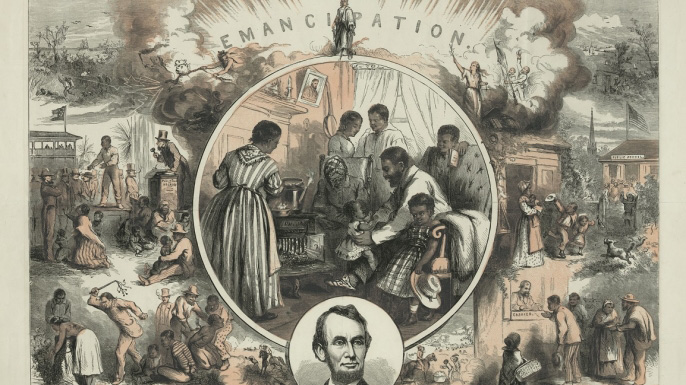

While the United States of America will celebrate its 241 birthday on July 4, officially known as Independence Day, there was another, less noticed, almost completely forgotten, “Independence Day” a little less than 89 years after the country was founded in 1776. That day was June 19, 1865 — and that day in the African-American community is called “Juneteenth.” What do you mean, President Abraham Lincoln, by executive order had signed the “Emancipation Proclamation” on Jan. 1, 1863, more than two years earlier?

While the United States of America will celebrate its 241 birthday on July 4, officially known as Independence Day, there was another, less noticed, almost completely forgotten, “Independence Day” a little less than 89 years after the country was founded in 1776. That day was June 19, 1865 — and that day in the African-American community is called “Juneteenth.” What do you mean, President Abraham Lincoln, by executive order had signed the “Emancipation Proclamation” on Jan. 1, 1863, more than two years earlier?

There were no smart phones, Internet or even long distance landlines in 1865. However, there were telegraphs, but for some odd reason, the slaves in many areas of the country were unaware they were free until long after the proclamation was signed by President Lincoln.

Granted, Lincoln’s proclamation was very limited. While it impacted between 3 million to 4 million slaves, primarily in the South, it didn’t free slaves held in Union areas or in slave states such as in Kentucky, Maryland, Delaware and Missouri that were not in rebellion. The proclamation also didn’t apply to Tennessee and other areas occupied by Union troops.

It wasn’t until Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas, that fateful day in June, with General Order 3, that slaves in that state were made aware of their freedom. The order stated:

“The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the con-nection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and free laborer.”

Stop for a minute and just imagine how the news hit the now former slaves. After living lives in captivity, they were now free and thus followed the celebration that we call today “Juneteenth.” Oh what a celebration it must have been.

News that slavery had ended spread like wildfire as many former slaves left the Texas plantations immediately for neighboring states, many looking for family members. Others left with no idea where they were going, but they left knowing they were free for the first time in their lives.

While some have foisted the idea that Lincoln freed Southern slaves to hurt the Confederacy, this was only partially true. In fact, the Confederate Congress had considered arming black troops from almost the beginning of the war and had vehemently denounced the idea, even at the behest of its greatest generals, including Robert E. Lee. The Union, on the other hand, through the work of Frederick Douglass, enlisted more than 180,000 colored troops.

By the time the Confederacy got around to enlisting colored troops in March 1865, the South’s choices were grim: Either have the enslaved fight for the Confederacy’s freedom or become enslaved themselves. Alas, it was much too late. Gen. Lee would begin the dominoes of Southern surrender on April 9, 1865.

Abraham Lincoln would be assassinated five days later, but that didn’t change the course of the war’s outcome. Lincoln died with the mantle of the “Great Emancipator” and the South is still trying to escape its history of slavery.

When Independence Day rolls around each year, African Americans have many reasons to celebrate, from the founding of the nation that our ancestors helped construct, from the Capitol steps of Washington, D.C., to the South’s prosperity and everything in between, but more so to a testament to the strength of our forbearers who faced down unspeakable horrors so that we could live a better life today. That’s a reason to remember and celebrate Juneteenth.

Written by Charles Richardson